Sustainable Development Goal # 3 that calls to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” has broadened the global health agenda as it not only builds on the progress made on the MDGs but also reflects a new focus on non-communicable diseases and the achievement of universal health coverage.

Photo: Tobin Jones Attachments area

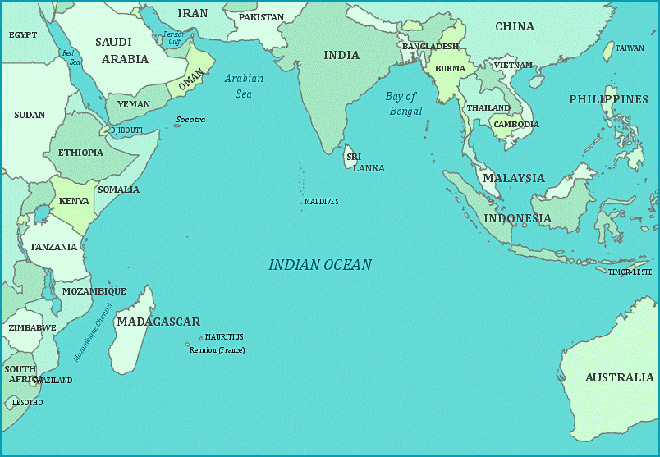

To achieve this goal by 2030, lower income countries need to partner with all key stakeholders and forge regional integration and cooperation. One possible regional integration could be between the countries in East Africa bloc and South-East Asia bloc that have lots of complementarities to benefit from each other. Countries that are specifically focused in each of these blocs are: Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda and Tanzania in the East Africa (call it “East Africa bloc”) while the countries in the Bay of Bengal Rim and the Himalayan Kingdom comprises Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Thailand and Sri Lanka (“BIMSTE bloc”). Each of these blocs is marked by geographical contiguity (see the map below).

Map 1: Geographic location of the two blocs

Before exploring the complementarities between the two blocs and gain perspective on their health sector engagement, it is important to understand certain commonalities and differences between these two blocs.

Contrasts and commonalities

Relative to the East Africa bloc, the BIMSTEC bloc has a much higher weight. It’s combined population of 1.67 billion constitutes around 22% of the world population (World Population Prospects 2017) and has a combined GDP (Gross Domestic Product) of USD 3.5 trillion. In contrast, the East Africa bloc has a combined population of only 254 million, representing 3.4% of the world population and has a combined GDP of USD 233 billion (IMF 2017).

Further, relative to the BIMSTEC bloc, the East Africa bloc is less developed. With the exception of Kenya which is a lower-middle income country, the other four countries in the East Africa bloc are low income countries (World Bank 2017-18). In contrast, all countries in the BIMSTEC bloc are lower-middle income countries with the exception of Nepal which is a low-income country and Thailand a which is an upper-middle income country. For this very reason, East Africa bloc receives higher ODA (official development assistance) than in the BIMSTEC bloc. For example, per-capita ODA for health sector in East Africa bloc varies from $8.1 in Mozambique to $3.4 in Kenya whereas the same varies from $ 2.8 in Myanmar to $0.28 in India (WHO 2018).

Agriculture plays a more dominant role both in terms of its contribution to GDP and to the labour force in East Africa bloc than in the BIMSTEC bloc. National poverty rates – rates calculated by the respective countries using their own definition of poverty – are significantly higher in the East Africa than in the BIMSTEC bloc. The differences in poverty rates in the two blocs become starker if one looks at the standardized definition of poverty, for example, population living on < US$1.9 per day (Wikipedia). On the human development index too, the East Africa bloc generally ranks lower than the BIMSTEC bloc (UNDP 2018). The BIMSTEC bloc generally fares better than the East Africa on most health indicators whether life expectancy at birth or maternal mortality or child (under five) mortality (WHO 2018).

However, the countries in both the blocs have a great deal of commonality too. For example, the structural transformation – a process whereby economic activities shift from lower productivity (agriculture) to higher productivity (manufacturing) sectors – of most countries in the two blocs is moving in unchartered territory (Paula, January 29 2018). Further, countries of both the blocs are facing similar development challenges: of building infrastructure, creating jobs for the youth, providing good governance, avoiding pitfalls of rapid urbanization, improving public service delivery and so forth. Governments in both the blocs are aspiring for higher economic growth to bring prosperity to much of its population. Indeed, countries in both the blocs are expected to grow faster than the world economy. People in both blocs are aspiring to have better quality of living that comes with higher incomes and improved access to basic services such as education and health. Being at the lower end of per-capita income, these countries are looking for a development trajectory that can give them speed, scale and deliver solutions at low-cost. Like other countries, both the blocs are counting on the ICT revolution that can make development solutions accessible and affordable.

Cooperation, engagements and partnerships

As the BIMSTE bloc is ahead, but not too far ahead, in its development journey than the East Africa bloc, the former can provide more appropriate development solutions to the latter. But the reverse could also be true. For example, Bangladesh, India and Kenya have emerged as hotspots of inclusive business models to address socio-economic challenges in a scalable and sustainable manner. Countries in both the blocs could benefit from these market-based, commercially viable and replicable models notably in the areas of agriculture, health and renewable energy (IFC 2016).

Both sets of countries have been seeking south-south economic cooperation to increase trading and investment opportunities between them. Even though the East Africa bloc has significantly smaller market today, it promises to be a growing market overtime -- both on account of its rising share in the world population which is projected to increase from 3.4% in 2017 to 5.3% in 2050 and the rising prosperity of its people. Further, the BIMSTEC bloc can offer technical assistance in framing policies, designing institutions, strengthening systems, building capacities, and so forth.

Indeed, the economic interaction between the East Africa bloc and India – the largest economy in the BIMSTEC bloc – has increased particularly since 2004 with the launch of Indian Development and Economic Assistance Scheme (IDEAS) that is based on the principle of development partnership for mutual benefit. Under IDEAS, India has been making investments in and extending concessional lines of credit to Africa. The East Africa bloc has been India’s favoured destination in making investments and extending lines of credit for some good reasons: presence of large diaspora, few regulatory hurdles, and widespread use of English (Chakrabarty, June 13 2018). Additionally, India has been giving grants under successive India Africa Forum Summit for capacity building, scholarships, training programs and implementing the Pan African e-Network project (Mishra, May 25 2018). India’s trade with Africa in general has gone up from around US$ 12 billion in 2005-06 to US$ 57 billion in 2015-16 and is expected to touch US$ 100 billion in 2018 (AfDB 2017). India has invested $52.6 billion in foreign direct investment in Africa between 2008 and 2016, accounting for nearly 21% of India’s total FDI outflows globally. However, much of India’s FDI to Africa has been to Mauritius and only small percent is to the rest of Africa. As a large part of India’s FDI to Mauritius is routed back to India, the actual FDI outflows from India to Africa is actually much smaller than what often gets reported (Chakrabarty, February 20 2018).

Even though a significant development and commercial engagement between India and the East Africa bloc exists at the level of government and the private sector, there is a huge scope for enhancing it. Health is one such area where this engagement has a potential to increase.

Health sector context

With the exception of Thailand and Sri Lanka that are outliers in the BIMSTEC bloc, the health sector challenges are not very different between the two blocs. Both the blocs are facing rising burden of non-communicable diseases even before they have addressed the communicable disease burden. Health systems in both the blocs are weak, marked as they are by shortage of human resource, low public financing of health and the consequent heavy reliance on out-of-pocket health spending, weak system of procurement and distribution of drugs, poor health infrastructure especially in smaller towns and rural areas and so forth (AfDB 2013).

Almost all countries in these blocs have mixed health system with significant presence of private providers in the delivery of healthcare services. Emerging models of public-private partnerships and the use of ICT revolution to overcome some of the systemic constraints to make healthcare accessible, equitable and affordable have raised hopes of improving country health systems. Even as India itself is learning from the success of countries like Thailand and finding its home spun solutions to its healthcare problems, it is also sharing its lessons with other countries. Indeed, some of India’s success stories in government sponsored health insurance for the poor, social marketing of health care and commodities hold valuable lessons for the African countries (IFC 2015).

India already has a significant commercial presence in Africa’s health systems. Over the years, India has come to be regarded as “pharmacy of the developing world.” India’s engagement in the health sector has been growing in exports of pharmaceuticals to African countries and business partnerships with hospitals in Africa. Cumulatively India has made FDI in African Pharma industry of US$ 246 million between 2008 to 2014 (James et al. 2015). Barring Rwanda, all countries in the East Africa bloc are among the major recipients of India’s investments in pharma. India has been one of the major suppliers of pharmaceutical products to Africa. India’s exports of pharma products have increased from USD 247.64 million in 2000 to USD 3.5 billion in 2014 (James et al. 2015). Given India’s comparative advantage in the manufacture of generic medicines, India could benefit from the growing pharma market in Africa which is projected to rise to USD 45 – 60 billion by 2020 (Ngangom, August 10 2016).

Further, high quality care at low-cost has made India and Thailand as popular destinations for medical tourism for many countries; India has emerged as a popular choice for many African countries. Besides pharma, medical tourism and ICT where engagement could deepen further, frugal innovations to serve the “bottom of pyramid” population in another area where East Africa bloc could benefit from India, and indeed from other countries in the BIMSTEC bloc. Aravind eye care and Jaipur foot and good examples of frugal innovations (Ngangom and Aneja, June 2016).

To deepen India’s health sector engagement with the East Africa bloc would require broadening of this engagement to include prevention-based health system as well as a different conception of the private sector so as to include social entrepreneurs, for example (Ngangom and Aneja, June 2016).

Many African countries that view India as a reliable partner, are seeking India’s help in wide range of areas of health sector such as medical education and training, treatment of specific diseases such as cancer, hospitals development and management, drugs and diagnostics and so forth. In fact, a few well-known corporate names in the Indian health space have become active in Africa too. Though the current level of engagement in the health sector between India and the East Africa bloc is significant and growing, it is nowhere close to its potential. The next few articles in the BIMSTEC-Africa Series on health will focus on specific areas of knowledge exchange on which future partnerships could be build.

0 Comments