Hamse Abdilahi is a Somali community activist and writer. He is a postgraduate student at Kellogg College, University of Oxford, studying for an MSc in Sustainable Urban Development. Here he tells us about his childhood in Somaliland and he shares ten lessons which he learnt on his way to being accepted to study at the University of Oxford. Hamse is also former Mandela Washington Fellow at the University of Delaware and a former Chevening Scholar at Bristol University.

I watched the majestic sight of sunrise from my half-empty Oxford-bound train window. Trying to figure out how my long educational journey culminated to that very dawn, I had a deep sense of appreciation for the great people who helped me along the way. The train’s automatic voice kept calling out the various stops it made along the Bristol-Oxford route. Even the cold October morning couldn’t dent my excitement to report to Oxford University for my course registration. As the train reached my destination, I grabbed my luggage and headed out of the small but otherwise packed train station. I patiently waited for a taxi at the parking space outside and it didn’t take long when a black taxi arrived. ‘Where?’ asked the taxi driver. ‘Kellogg College’ I answered.’ ‘Oh Kellogg’ smiled the taxi driver implying his familiarity with my destination.

At Kellogg College, I grabbed a cup of coffee and a biscuit. Students, dressed in black gown and hat, a white shirt and bow tie, continued to gather at the college for the matriculation day. Matriculation is an elaborate ceremony and an old Oxford tradition which is normally done in the first week of the Michaelmas Term – the first term according to the Oxford language. It is the last step of the University’s long and rigorous admission process where students are formally admitted to the various colleges they were accepted to. We marched to the Sheldonian Theatre where the Vice Chancellor read a centuries-old brief speech in Latin and English welcoming students to the university and wishing them a successful life. We then marched back to Kellogg for a group photo, lunch and conversations with students and college staff over tea. Despite the long day, it was a sigh of relief for me, for I was finally and officially an Oxford University student and a proud member of Kellogg College. But my pride was tempered by humility because of my very humble background.

Kellogg College is Oxford University’s largest college by student size and the most international of all of Oxford University’s 38 colleges. A college does not mean a department or a faculty as many would expect, but rather an autonomous and self-governing corporation within the university. It is like a government within a government. The collegiate system entails that all teaching staff and students must belong to one of the colleges. Colleges have substantial amount of responsibilities which include administering houses of residence and tutorials. A typical Oxford college would comprise of a dining hall, a chapel, a library, a college bar, postgraduate and junior common rooms, lodgings for the dons etc. However, the university departments run the traditional tasks such as organising lectures, examinations, laboratories and central libraries.

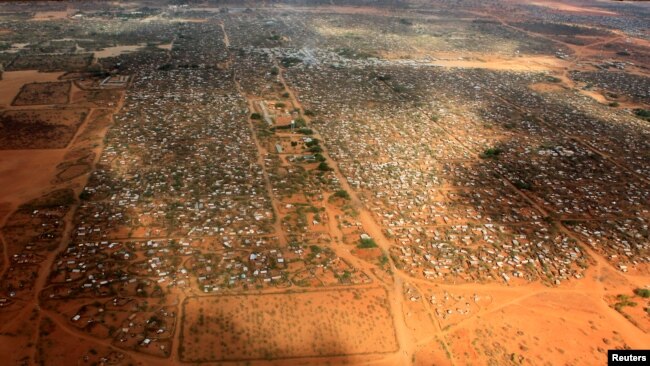

My long journey to Kellogg College wasn’t all rosy. Raised by my maternal grandmother, I started school in a roofless building in Hargeisa in the early nineties. The city suffered a complete and spectacular devastation in the Somalia civil war. Occasionally, on my way back from school, I would come across people bleeding profusely after their legs were blown off by mines. I watched them helplessly as they were carried away on to the back of truck to be transferred to the nearest hospital which had little or no medical supplies. ‘Maybe I would help them when I grow up’ I would console myself and head home. The roofless school was short-lived as another civil war broke out forcing us to leave the town. Luckily, in several months, the war stopped, and my schooling was never interrupted again. This, however, was not the case in southern Somalia, where the conflict has endured and lasted to date.

The secessionist agenda which Somaliland pursued following the seemingly irreversible state collapse in Somalia has had the most dramatic effect on me and my generation. In one way, it spared us from the violence that consumed the rest of Somalia, but it also left us in an awkward situation. The idea of living in an internationally unrecognised state is unusual. There are only a little over a dozen unrecognised or de facto states in the world. Lacking official international recognition means that there are no diplomatic missions in the country, you can’t travel outside the country since you lack a valid and recognised passport, the government cannot go into formal trade deal nor binding international agreements with other nations and international organisations. In other words, you are stuck, the country is stuck, and everybody is stuck. And ever since, the country grappled with poverty and painstaking state building in the face of international diplomatic isolation. Lacking in infrastructure and near non-existent public services compounded the austere life in Somaliland. Working hard in school was the key to escaping not only the poverty but also breaking free from the shackles of that diplomatic ‘cage’. Despite such circumstances, I feel fortunate that both my undergrad and postgrad studies came through a merit-based scholarship all of which were competed nationally.

How did you end up at Oxford? Did you ever imagine going to Oxford? These are the common questions people ask me every time. Of course, I imagined being at Oxford, but I can’t point out a single factor which I can single-handedly attribute to my acceptance to Oxford. My life was a product of hard work, but also of luck, like meeting the right people who believed in me at the right time, giving me opportunity at the right time, all of whom were important in the trajectory I had over the years. My fundamental being hasn’t shifted after my acceptance to Oxford. I am still the same person.

Below are ten key lessons which I picked up along the way and through them you can understand the principles that sustained me during my journey to Oxford.

1 Master your English

Very early on, I understood that if I want to be successful in my studies, I have to master the English language. But having a good command of the English language wasn’t easy. English is my third language. Arabic was the medium of instruction in my primary school. Somali was the only language spoken at home, in the local media and in the wider society. As I progressed to high school, an afternoon English tuition class greatly helped me. I started to read English grammar books to improve my English. But it was my avid listening to the BBC World Service radio which proved most crucial in improving my English. The BBC radio programs also significantly improved my understanding of the world, my thinking horizon and my perspective on many global issues. The level of one’s English affects the quality of writing and the effectiveness of communication with people, all of which are critical in achieving success. Having good English has a bigger significance than a simple communication in today’s world. Most academic books are written in English, many of the best universities in the world are in English-speaking countries of the Western world, the world’s two biggest financial capitals are in English speaking countries and most international organisations have English as their medium of communication. I am also aware that I come from a British colony and I resent the English colonisation of my homeland, but I am also aware that English is key in navigating the current world order which, I believe, is not going to change anytime soon at least in my lifetime. I think there is nothing wrong with learning your former colonial master’s language and use it to your own advantage. As I passed by the Oxford English Centre one afternoon, it reminded me the Oxford English Dictionary, the world’s most trusted English dictionary. I held the Oxford dictionary in high esteem as it helped me greatly when I was an English language student.

2 Focus, aim for the best and believe that you are meant and destined for greatness

Focus as you plan to the end. But aim for the best and for the highest. According to most studies, great people and historic figures led normal lives before they took a dramatic decision at various times in their lifetime which made them great. Many of them did after the age of forty while others did it considerably later in their lifetime. This means that anybody can achieve greatness anytime in their lifetime. I want to be great for a great cause. But greatness can come in many forms. From a meaningful community service and empowering the girl child to freeing your people from the shackles of poverty and destitution and fighting environmental degradation, the opportunities to be great are endless. A genuine belief that you can be great and that you should do great things must underpin one’s own view in life. This is important because it affects your day-to-day decisions and priorities in life. Believing you are destined for greatness affects the way you conduct yourself and prevents you from bad behaviour such as political corruption.

3 Build your confidence to the level of believing you are the best in the world

Many people often ask me where I got that confidence. Again, it is a difficult answer. I wasn’t a confident person all my life. I have got my own insecurities and uncertainties. In my early years in school, I was shy and unable to speak before class. But I strove not to let them undermine my confidence to the level that I would believe that someone else can do better than I could. Today, I am invited to speak before many people. Confidence can be grown. But how does someone build his/her confidence? This is the million-dollar question. My answer is simple though controversial- first believe you are the best in the world in your respective field or area of interest. I won’t be apologetic on this point however absurd it may sound to many people. But one cannot be good on everything. Instead you’ve to identify a particular area of interest. You’ve to believe that you have the potential to be the best in that area. You also need to voraciously read about that field, contact the leading scholars in the field, chat with them, keep up with the latest literature, critique the direction of the current debate and come up with an original hypothesis or scientific discovery if you are in scientific research field. Overconfidence shouldn’t lead you to arrogance and close-mindedness, but be dynamic and open to change when facts against your position pile up. Be open to learn, but deep inside, believe you are the best while not uttering it publicly.

4 Genuinely acknowledge your biggest fear

My biggest fear in life wasn’t a financial or a political career failure; it was simply leading an unremarkable life and dying in obscurity. To be honest, I haven’t publicly shared it before, but I know it is my biggest fear. I always wanted to leave behind a meaningful legacy for my people and the world. I have always had a deep disdain for mediocrity. While I am not sure what that legacy would turn out in the end or whether I would even live long enough to see it or make it, but it is my hope that it would be profound. It is this very fear that drives me every day to move ahead so that I can stay ahead.

5 Develop a fierce competitive spirit

My competitive nature started largely with working hard to perform well in school, but it stayed with me right through to adulthood. Later in life, it became instrumental in motivating me to compete for more important matters in life than finishing top in class. A competition for a job, a scholarship or a cash grant would motivate me and I would put all my effort to win it. If I won it, it felt exhilarating, when I failed to get it, I would attribute it to my approach to the competition but not to my ability. I hardly took it personally or lost momentum. And I would most likely run again for the same thing or run for a bigger job, a better scholarship or larger grant, and most likely I would land on one. For example, when I first applied to Oxford University, my application was rejected. I had two options then: to give up my pursuit for a place at Oxford and believe that maybe I am not an Oxford university material because I am not white and rich, or to refine my application and apply for a slightly different course in a different department, which I did. When I submitted my second application, in less than a week, I was invited to an interview by the university which was successful. So, my lesson is if you lose a competition, don’t take it personally, but blame your approach to the competition, revisit it and run again, chances are that you will nail it this time and harder. You will finally reach a stage where you will enjoy any competition regardless of winning a trophy. Some competitions and applications cost money. Don’t be too mean and withhold a small entry or application fee. I often see people who can’t take a small financial risk to go for a big prize. My advice is don’t be mean. You’ve to financially stretch yourself to go places. Also you’ve to push the boundaries and prove your critics wrong. Don’t just settle for a good job and a place at university, go for the best job, create the best business, aim to join the best university, meet the best people. In other words, push the boundaries and more importantly prove your critics wrong. There is nothing that gives me more pleasure and satisfaction than not only proving my critics wrong but also very wrong. When I had the car accident and during the lengthy hospitalisation that ensued, many people wrote me off. I did my best to prove them wrong. When I left the hospital, I was a changed man. Since then, I went back to work, travelled to New York, London and Moscow without carrying a North American or European passport. I had the opportunity to shake hands with President Obama in Washington D.C in 2015. I won a postgraduate British scholarship, I got accepted to Oxford, and more importantly I got married to the love of my life whom I am happily living with in the UK. I am not listing my progress to boast about it, but I am sure they utterly surprised my critics.

6 Believe that you can rise above the circumstance of your birth

Coming from Somaliland isn’t only coming from a place ranked bottom of the international socio-economic index. It simply does not exist on the world map. If you complain of coming from a poor country, I complain of coming from a country that doesn’t officially exist where you feel an outsider to the world order. If you complain of living in a city council house and live on state benefits, I never saw a welfare state in my life. If you complain of going to poor schools in poor neighbourhoods, I went to a roofless school and I suppose yours had some roof at least. If you complain about belonging to a patriarchal society, I too had my first female teacher in college. But when you rise above such circumstances, don’t just appear in the media and criticize your community wholesale as many people do. Instead, go to the grass root level, talk to the people and change your society from within and help them be more forward thinking so that they embrace positive change.

7 Be open-minded

I grew up in a homogenous society where everybody looked like me, spoke the same language and belonged to the same faith. I struggled to be an open-minded person. Getting rid of certain prejudices wasn’t easy. But finally, I like to believe that I did away with them or at least most of them. I like to engage with people, have simple conversations, ask them about their countries’ culture and history. After every discussion, I realise how we, as humans, are astonishingly similar in our emotions, psychology and aspirations.

8 Use your background to your own advantage and work twice harder

If you are the only black person in a predominantly white institution or the only woman in an all-male workforce or the only disabled person in all-able-bodied environment, use that to your own advantage. When I was interviewed for my UK postgraduate course by a British diplomat in Hargeisa in 2016, she asked me why I chose to do MSc in Public Policy at Bristol University. I told her that I trained to be a clinician in my undergraduate degree but shortly after leaving medical college and a few months into my medical practice, I was involved in a car accident and I spent many months in hospital, and that the accident made me experience both sides of care. I also told her that I came to understand to importance of having efficient public service such as health care and education and that is why I wanted to do MSc in Public Policy. ‘I want to make our government efficient’ I told her. ‘Ok, got it’ nodded the apparently convinced diplomat, and in a couple of months, she sent me the acceptance letter to come to the UK and do my course at Bristol University. In this example, I used the accident, a tragic moment in my life, to my own advantage and it worked.

9 Believe there are better days ahead and seize the opportunity very early

My life has seen its fair share of adversity from poverty and displacement to physical pain and lengthy hospitalisation and most of them in childhood and at the prime of my youth. I have always had a deep sense of belief that it is not yet over and that there is a better day ahead. I don’t mean that I am a tough man and that I can overcome any a serious challenge that life throws at me, but I strive to be optimistic about life. There are many times that I feel blue. I often get rejections to my applications which also disappoint me. As humans, we are emotional beings. There is nothing wrong with feeling sad, angry and depressed in certain situations, but continue to believe there is a great day ahead of you. Such belief must be grounded on unwavering hope that there is not only a better day ahead, but also a much better day. Seizing opportunities is also crucial. Some opportunities come and go like a flock of birds and sometimes never to return. For example, when I came back from America after finishing my summer fellowship at the University of Delaware, I understood it was the right moment for applying for an overseas postgraduate scholarship. Also, when I finished my masters at Bristol University, I knew this was the right moment to apply for my dream university – Oxford. It is crucial that someone recognises these opportunities as they pass, and never let them slip away, for we live in a very competitive world as one needs to outsmart his counterpart.

10 Don’t be intimidated by the disempowering statistics and big names

As joining Oxford was always a childhood dream, I used to read the news and reports about Oxford University. But most of the reports demotivated me. For example, I read that 42 out of the 56 UK prime ministers went to Oxbridge universities- Oxford and Cambridge with Oxford’s Christ Church College producing 13 UK prime ministers, more than any other Oxbridge college. The two universities have also produced many world leaders such as Bill Clinton and Australia’s Tony Abbott. Most UK members of parliament, most high-profile BBC journalists, most UK cabinet members, most CEOs of companies went to Oxbridge. Even the Governor of the Bank of England went to Oxford. These staggering statistics demonstrated the class culture entrenched in the English society of which I do not belong. But I kept believing that I can defy this culture and still go to Oxford. So, when you are told to lower your expectation because of your background, don’t bow to that. Never believe in a disempowering statistic or data.