The Kisii tribe of Kenya is among one of the earliest Bantu settlers in modern-day Kenya. They are the dwellers of the highlands east of Lake Victoria. Accounts concerning their points of origin before situating themselves in their present locality are of varied nature; some scholars claim they came to their present settlement from ancient Egypt whilst others claim they settled from Uganda.

The Kisii tribesmen are predominantly farmers and craftsmen; economically viable activities that put food on their table and accord them media of exchange for those goods and services they are unable to produce and provide for themselves. Kisii tribesmen follow a tradition of fathering a lot of children, partly to aid the agro-culture on which they subsist and partly to carry on the tribe’s legacy and cultural heritage. They are a well-educated and highly skilled cohort whose endeavours are characterized by order, structure and precision; functional features of one of their most revered practitioners…

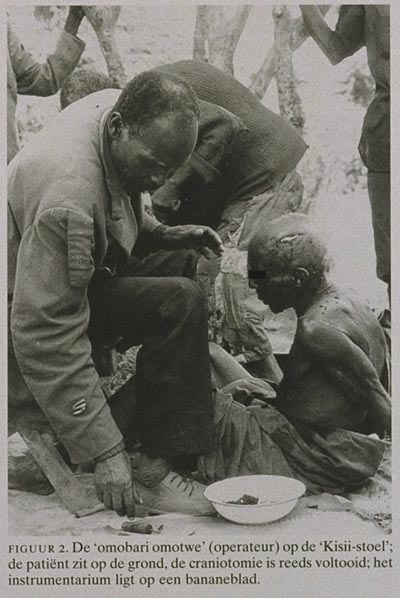

‘Omobari Omotwe’ is the Kisii word for a head surgeon. These highly knowledgeable men in the medical art of ‘craniotomy’ and highly skilled in those medical practices that bring to bear the practical application of their knowledge are recorded to have practised their craft with astonishing success long before ‘official’ means of documentation were made feasible.

Omobari understudies a more advanced practitioner who is usually a relative, by years of study and apprenticeship ordered along the lines of increasing difficulty given each assignment, a young Kisii can rise with dedication, determination and hard work to become Omobari over the years. And this spells out wealth, prestige and recognition for the said individual and his family.

Omobari’s craft is tailored towards the resolution of; acute cranial trauma and post-traumatic headaches. The cases brought to Omobari tend to have causes rooted in accidents and violence. Accidents can range from hitting one’s head against the low lintel of a Kisii hut to being struck in the head with a hoe on the farm unintentionally. Violent actions leading to seeking out the services of Omobari can also range from a severe blow to the head using a blunt object on the field of war and the use of head trauma inducing ‘weapons’ such as wooden clubs in severe cases of sibling rivalry or disputes among wives.

When a patient is brought before Omobari, he foremost says a prayer for guidance and then palpates the head of the patient to pinpoint the spot on the head where the incision will be made. Patients are given herbal concoctions before, during and after the operation to; minimize pain, boost immunity, sterilize the open flesh on the head and to stop bleeding and the patient from smelling the scent of blood during the procedure, because it can have a nauseating effect on the patient in question. The use of herbs thus improves the efficiency and overall effectiveness of the entire procedure.

In the case of acute cranial trauma, this is usually caused by a direct blow to the head by the use of blunt objects as mentioned earlier. The destructive effect of such deathly encounters is easily noticeable by the experienced and highly skilled Omobari who quickly but adeptly cuts his way into the skull of the affected area. This is to help remove all fractured bones and smoothen out the fractured edges to allow for the affected area to heal. All these are done with an astonishing success rate as all those modern medical practices that guarantee success in any surgical procedure are duly and methodically observed by Omobari and his apprentice(s), except within the parlance of his cultural traditional practice which is equally valid nonetheless.

Cases arising from post-traumatic headaches tend to tow the lines of examining the head critically by Omobari to help him identify which point on the head to open in order to resolve the case in question. Once Omobari is satisfied with the site located, he employs his homemade tools in digging into the area beneath the skull in his bid to drain out what has been named; ‘bad blood’. This is most probably non-circulating blood collected in an area beneath the skull that has gone bad. A critical examination of the site is also carried out to make sure there are no fractured bone fragments in the region, as these can puncture delicate blood vessels and lead to the same or more complicated medical conditions.

There is little to no known case of infection over operated areas given Omobari’s art. Furnas et al (1985) reported Omobari and his apprentice(s) as neat and orderly when engaged in their line of duty.

The craniotomy undertaken by Omobari and his team of medical specialists is very effective in the treatment of acute cranial trauma and post-traumatic headaches. Their Maasai neighbours are known to visit the Kisii Omobari for treatment on occasions. The procedure is again reported by Furnas et al (1985) to have a strong placebo effect. Thus the Omobari and his team of medical specialists do not only resolve the physiological anomaly associated with reported cases but its psychological dimension as well.

The Afrikan in view of these must make highly conscious efforts to foremost safeguard his continent within which can be found highly advanced practices, and also learn to safeguard him/herself by whom these advanced practices are made manifest.

Reference

Furnas et al. (1985). Traditional craniotomies of the Kisii Tribe of Kenya. Annals of Plastic Surgery. Vol 15 (6).

0 Comments